2013 will be remembered for the incredible size and scope of the social mobilization that gripped Brazil. People on the streets were witness to the dis-proportionality of police actions.

Article19 – report: The countdown to the 2014 World Cup has been marked by a series of demonstrations across Brazil, with hundreds of thousands of Brazilians protesting against government corruption, unaccountable decision-making and the vast expenditure used to host the games, money which they believe would be better spent on public services. (note: please follow page links at bottom for full article)

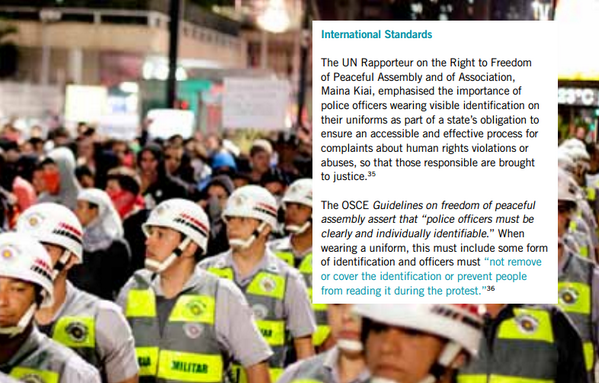

Research published in Brazil’s Own Goal shows that the state’s response to these demonstrations has been one of increasing repression and violence, more suited to Brazil’s years of military dictatorship. Police are using excessive force against demonstrators, including highly indiscriminate use of potentially lethal weapons such as rubber bullets and tear gas. A large number of police officers have been spotted removing their identification during the protests and refusing to identify themselves when asked so as to ensure their actions cannot be traced back to them. There have been thousands of arbitrary arrests and the practices of preventative detention and prior restraint are rife.

To compound the crackdown on freedom of expression, several bills have been proposed in congress to criminalize demonstrations, including increasing the penalty for crimes related to damage to property and persons when these happen in demonstrations, the criminalization of the use of masks in protests and the closure of public roads.

Furthermore, the General World Cup Law, which was approved in 2012, already prohibits demonstrations that do not contribute to a so-called ‘festive and friendly’ event, meaning that some protests could be considered illegal depending on their nature if held anywhere near a stadium, which of course are mainly in highly populated urban areas.

The right to protest and freedom of expression is protected under international law, and yet Brazil’s Own Goal shows that these rights are being stripped away in the country. ARTICLE 19 is calling on the Brazilian government to ensure the right to protest and freedom of expression are protected, by introducing a new law to regulate the use of police force during demonstrations, which should follow international standards. This law should also ensure policing at protests is designed to safeguard the people’s right to protest in a safe manner.

There have been widespread protests in Brazil, many of them strongly related to the country’s preparations for its forthcoming hosting of both the World Cup and the Olympics.

However, these protests were not isolated incidents but a continuation of Brazil’s recent history of protest, and of a more widespread backdrop of protest regionally and globally.

Brazil’s recent history of protest

For the past thirty years, Brazil has experienced intense social mobilisation which has successfully led to major changes in the country’s social and political structure including:

Direct Now: Starting in 1983, this movement brought millions of people onto the streets and contributed to the country’s return to democracy in 1984, marking the end of its 20-year military dictatorship.

Movement of Painted Faces: the 1992 protest involved hundreds of thousands of people in the cities of São Paulo, Brasilia, Recife, Salvador and Rio de Janeiro. It culminated in former President Fernando Collor de Melo’s impeachment for corruption.

The Freedom March of 2011 saw thousands of protesters and more than 100 collectives taking to the streets in 41 Brazilian cities, protesting against police repression of demonstrations.

During this period, a vibrant range of social movements has grown up, organising and mobilising around several issues: the landless, women, unions, and minorities such as LGBT. Every one of these movements has, at some point, been denied the right to freedom of expression.

The March for Agrarian Reform in May 2005, for example, ended with police and protesters clashing, injuring more than 32 protesters and 18 police officers.

“ We continue with a police model we inherited from the dictatorship – and the manuals with which the police are trained and the way they deal with people in the demonstrations and on the streets are remnants of that regime.” Maria do Rosario Nunes, Brazilian Minister for Human Rights under Dilma Rousseff14

Police used firearms in at least eight protests,57 resulting in the death of one protester. A number of other people also died as a result of the protests:

Cleonice de Moraes was at work as a cleaner in the city of Bethlehem on the night of 20 June and inhaled tear gas during the confrontation between police and protesters. Cleonice, who was hypertensive and on medication, had a cardiac arrest and died on the morning of 21 June.

Marcos Delafrate, a student, was hit on 20 June, in Ribeirão Preto-SP, by a vehicle which crashed into the protesters, crushing Marcos and 11 others.

Valdinete Rodrigues Pereira and Maria Aparecida were blocking the BR-251 highway in Goiás with tyres on 24 June. A vehicle drove towards the group of protesters, ran them over and left without

stopping.

Patrick Paulo Silva de Castro, a student, was hit by a taxi on 26 June, in Teresina-PI while jaywalking. He was left with a cerebral oedema and died about two weeks later.

Douglas Henrique Oliveira, during a confrontation with police on 26 June in Belo Horizonte-MG, tried to jump across a flyover and fell. He died the next day as a result of his injuries.

Young unidentified man was hit on 27 June in Guaruja-SP, when a truck tried to change direction to avoid a demonstration and hit two young men, one on the back of the other’s bike. One died and the other survived with serious injuries.

Renato Kranlow broke through a demonstration in his truck on 3 July in Pelotas. Protesters threw a stone at him, through the truck’s glass.

Research highlights a number of common concerns about the police and their actions:

• Police officers lacking identification • Arbitrary arrests and detention, including detention for questioning, practically unheard of since the end of the military dictatorship • Criminalisation of free expression, treating protesters as offenders • Pre-censorship, banning, for example, protesters from wearing masks or carrying vinegar • Dis-proportionality of police action and prevention of monitoring • Use of lethal weapons and the abuse of less lethal weapons, resulting in several deaths • Use of undercover police “agent provocateurs” in demonstrations, sometimes causing and encouraging unrest and violence • Police, Abin (intelligence agency) and Army vigilantism on social media, police recording protests and preventing protesters from

monitoring police actions • Concern for property rather than the safety

of protesters • Threats and kidnapping.

ARTICLE 19’s survey of all the 2013 protests, based on records and reports disseminated in Brazil’s major media outlets in the country,

counted the following numbers of violations and incidents of violence:

Quelle: Revolution News